Coaches and other leadership within sports have the ability to greatly impact athletes, either positively or negatively, and must use this influence for the betterment of sport and athlete health. Recently, an article published in the NY Times described the toxic coaching environment imposed on track and cross-country athletes at Wesleyan University. In response to the perpetuated culture of body shaming, “fat talks” (described as conversations in which the coach encouraged weight loss to run faster), and rampant eating disorders/disordered eating, former student-athletes/alumni of the team wrote an open letter to the Wesleyan community to demand change.

Sadly, this type of abusive coach-athlete relationship is not unique- in fact, the mistreatment of female athletes is pervasive in collegiate and professional athletics, and not isolated to cross-country and track (see articles listed below). Weighing athletes in front of their teammates. Commenting on weight in front of teammates. Telling athletes that thin equals faster. Encouraging extra exercise to lean out. The list of abusive words and behaviors goes on. This is unacceptable— the health of all athletes MUST be a top priority for coaches.

Unfortunately, exercising women are particularly susceptible to disordered eating behaviors, as it is reported that up to 60% of these women display subclinical disordered eating (Gibbs, Williams et al. 2013). For collegiate and professional athletes, where the sporting environment provides unique pressures related to performance, research suggests that more than a quarter of female collegiate athletes exhibited disordered eating symptoms (Greenleaf, Petrie et al. 2009), while almost 50% of elite athletes women met the criteria for clinical eating disorders (Torstveit, Rosenvinge et al. 2008). Importantly, pressure from coaches is commonly reported among female athletes (Reel, SooHoo et al. 2010), with specific pressure on body weight and appearance which has been shown to predict increased body dissatisfaction at the end of the season in 325 NCAA Division 1 athletes ((Anderson, Petrie et al. 2012)). Encouraging weight loss with critical comments regarding body shape, body size and body composition can send athletes into a downward spiral of disordered eating behaviors, with the potential to manifest as clinical eating disorders.

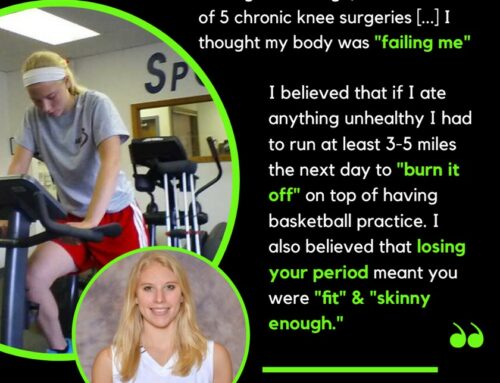

The detrimental consequences to mental and physical health are real and have the potential to stick with female athletes for the long run. Altered eating behaviors or psychological problems leading to reduced food intake, can lead to energy deficiency and worsening physiologic complications. When persistent, chronic energy deficit can result in severe menstrual dysfunction (i.e. irregular cycles called oligomenorrhea or or no menses for three months of more called amenorrhea) and decrements to bone health (i.e. low bone mineral density and stress fractures) (De Souza, Nattiv et al. 2014). In fact, amenorrheic athletes have been reported to have lower BMD, and increased fracture risk compared to menstruating athletes (Ackerman, Cano Sokoloff et al. 2015)- in some cases the bone loss may not be fully recovered (Drinkwater, Nilson et al. 1986).

A culture shift in collegiate/professional athletics is crucial in order to protect the health and well-being of female athletes.

By hearing your voice and stories, others will feel empowered to come forward. You are not alone.

Your interactions with athletes can have long lasting consequences.

- Instead of using food logs to shame or guilt your athletes into unhealthy eating behaviors/ relationships with food, coaches, you should encourage athletes to work with a qualified professional (sports dietitian/nutritionist) to develop a nutrition plan to support their exercise and health needs.

- Do not focus on body weight or body composition. Low body weight and body fat is not a sign of athletic success, and in many cases indicates that the athlete is not fueling for optimal performance. Instead, help your athletes create a healthy relationship with food and foster an environment for body positivity.

As recommended by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association:

“Develop policies that clearly define the appropriate responses of coaches when dealing with athletes regarding body weight issues and performance. Coaches should not be allowed to disseminate improper weight loss advice, conduct mandatory weigh-ins, set target weights, or apply external pressure on athletes to lose weight.” (Bonci, Bonci et al. 2008)

-Nicole Strock MS, Triad Team Content Creator

To read other articles highlighting this issue in collegiate and professional sports:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/07/opinion/nike-running-mary-cain.html

https://www.nj.com/rutgersfootball/2018/08/rutgers_petra_martin.html

To read other resources: