What is the Female Athlete Triad?

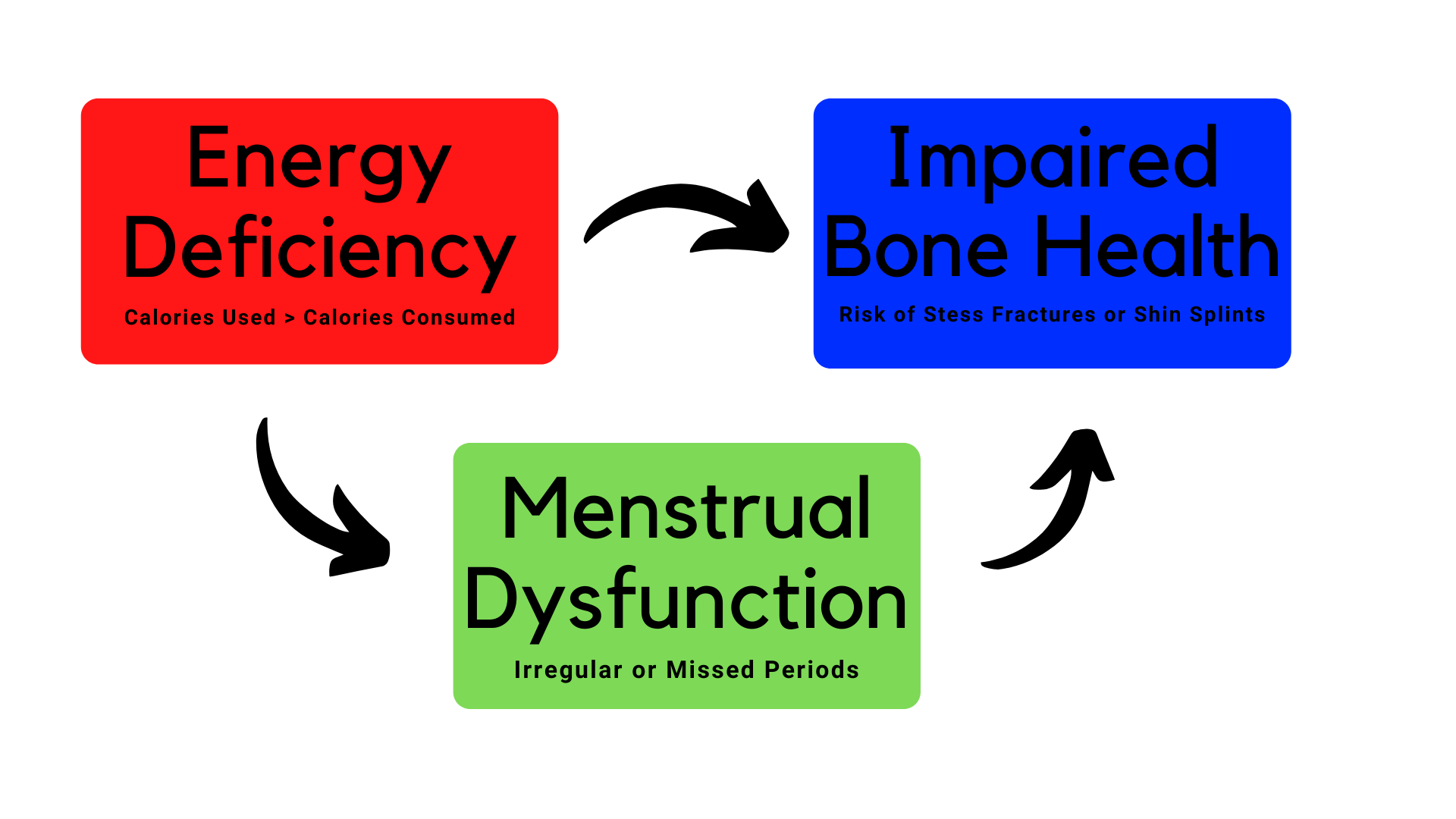

The Female Athlete Triad (Triad) refers to three health problems that are related to each other: Energy deficiency (“under-fueling”), menstrual disturbances, and poor bone health in exercising women [1-5]. Menstrual disturbances include irregular (oligomenorrheic) or missed periods (amenorrhea). Poor bone health includes low bone density for your age (i.e., weaker bones) and can lead to bone stress injuries, stress fractures and osteoporosis. The Triad and its associated health concerns require prompt medical attention and having just one part of the Triad is enough for any girl or woman who wants to stay active to seek help. Luckily, the key to avoiding menstrual problems and building strong bones is simple — eat enough calories to fuel your body during exercise and at rest.

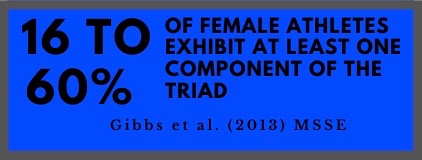

The Triad is very common among exercising women. In fact, a systematic review of research literature including 65 studies in 10,000 women, reported that up to 60% of exercising women had at least one Triad-related condition [6]. These are serious health consequences and if left undiagnosed or untreated could result in lifelong implications for the athlete or exerciser, particularly regarding bone health- we still do not know whether bone loss can be completely recovered [7-12]. Importantly, you’ll see that decades of evidence-based research have contributed to our understanding of the Triad.

Components of the Triad

Energy deficiency occurs when active girls and women routinely consume fewer calories than they burn during exercise (energy intake < energy expenditure). Energy deficiency is the driving force of the Female Athlete Triad [2-4]. In response to energy deficiency, your body alters important systems, including growth and reproduction, in an attempt to conserve vital organ processes that are most essential to life [13, 14]. If this energy deficit is too large, your body will have too few calories or too little energy left over to maintain other normal functions. Some indications of energy deficiency can be changes in body composition (low body weight, body fat) and metabolic hormones [15-17].

Sometimes, female athletes slip into this under-fueled state by:

-

-

- Disordered Eating & Eating Disorders [18-20]: Some women try to lose too much weight or lose it too quickly in order to look or perform better or under-eating by skipping meals, avoiding all foods that contain fat, or they eliminate lots of foods without making healthy substitutions

- Inadvertent under-eating : Some women simply do not realize how much energy they burn during workouts and they do not eat enough to maintain a healthy weight.

- Using too much exercise relative to their caloric intake in order to lose weight quickly, which can create an excessive energy deficit.

-

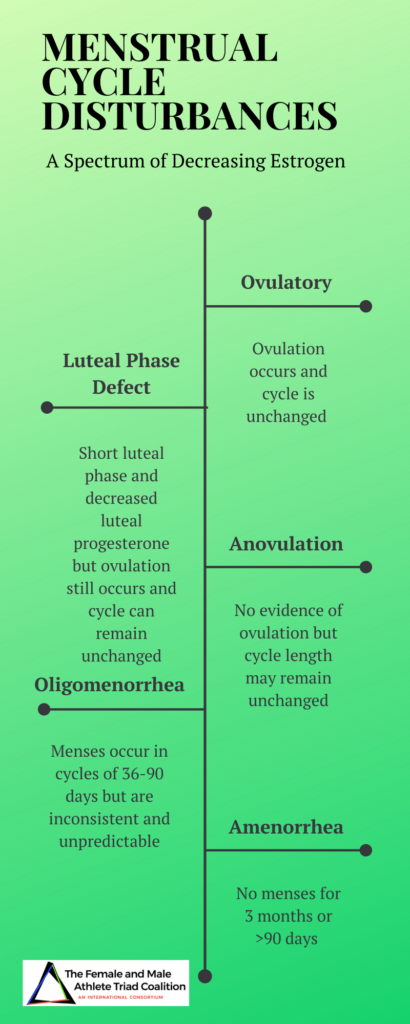

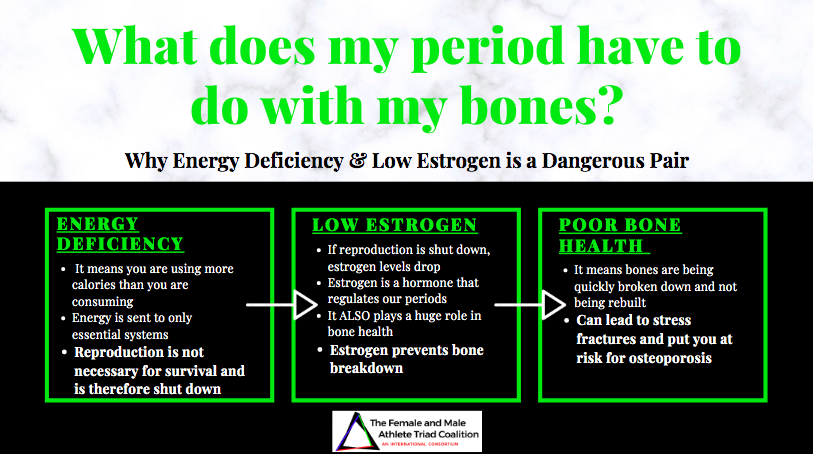

Energy deficiency disrupts the reproductive system in otherwise healthy active girls and women [2-4]. When the body is in a state of energy deficiency, the HPG (hypothalamic pituitary gonadal) axis is suppressed [21-23], and can lead to menstrual disturbances [24-26]. Consequently, many women may experience a spectrum of menstrual disturbances ranging from irregular periods to amenorrhea (a complete loss of menses) [16, 27, 28]. Irregular or less frequent menstrual cycles is called oligomenorrhea. Even more worrisome is when three (or more) menstrual cycles in a row are missed, called amenorrhea. Eating too few calories can also delay the onset of menstruation (i.e., first period), so that a young woman does not begin having periods by age 15 (delayed onset of menarche). When periods are less frequent or missed, the body begins to make less estrogen- a hormone that is absolutely necessary for building strong bones and reproduction. Any menstrual irregularities must be diagnosed by a physician in order for proper care to be provided.

Due to the changes in hormones that are associated with energy deficiency, your body is not able to replace old bone cells with new healthy cells. During this time, you are at risk for poor bone health. The situation is even more alarming for physically active girls with irregular periods during their peak bone-building years (puberty to age 20) [29]. Despite the positive bone-building effects of exercise, these under-fueled girls actually fail to build all the bone that is expected (cite). It remains unclear whether this “lower-than-expected” or overall decrease in bone mass is permanent or if full “catch-up” is possible once menstruation begins [7, 10]. Losing bone mass or bone density faster than you should sets the stage for stress fractures and the early onset of osteoporosis (weak bones that break easily). Energy deficit athletes can also present with suppressed bone turnover [30], impaired bone quality [31]. increased bone stress injuries [32-34], stress fractures [35, 36], and low bone mineral density [37-39]. Additionally, Bone loss is made worse by energy deficiency and under-fueling and getting too little of important nutrients like calcium and vitamin D. In fact, energy deficiency and estrogen deficiency from menstrual disturbances can have a combined impact on bone health, disrupting bone metabolism through uncoupled bone turnover [40-42] where there is an increase in bone resorption (breakdown) and a decrease in bone formation from a lack of energy, results in weakened bones over time.

What are the risk factors for developing the Triad?

There are many factors that put someone at risk for the Triad [2, 3]. Being aware of these risk factors allows you to stay ahead of the Triad and aid in prevention.

Dieting at an early age

Disordered eating habits (such as skipping meals)

Being unhappy with your body type

Perfectionism

Believing that losing weight (or body fat) at any cost will improve performance

Taking part in sports that favor a lean body size or shape (like gymnastics, figure skating or long distance running) or sports that have weight classes (like rowing) or revealing uniforms (like swimsuits or volleyball uniforms)

What are the signs of the Triad?

You do not need to exhibit all three components of the Triad at the same time to be at risk for adverse health outcomes [2, 3]. Frequent or deliberate attempts to lose weight or decrease body fat quickly or to look “more toned” or “like an athlete should” often result in disordered eating patterns and under-fueling.

Possible indicators of the Triad that need to be evaluated by a sports-minded health professional include:

Irregular or absent periods (or difficulty becoming pregnant)

Stress “reactions” or fractures

A preoccupation with weight or body size and shape that interferes with normal eating habits

Noticeable weight loss

Excessive or compulsive exercise habits

How is the Female Athlete Triad treated?

Treatment will look different for every individual, but we have collected a few tips on how exercising women who are experiencing the Triad can reach out to medical professionals to get the help they need:

Seek a team of experts who provide medical care and nutritional counseling

See a psychologist or other counselor to seek help for any disordered eating thoughts or anxiety

Educate yourself on how to maintain a healthy lifestyle by eating enough calories to cover the amount of energy expended through exercise

If your periods are irregular or you have not had a period for over three months (or have not started your period by age 15), see your doctor immediately.

This is NOT normal.

Birth control (oral contraceptives) are not an appropriate treatment. While it may appear that you “get a period” with OCs, these medications are not getting to the main cause of menstrual dysfunction, which is energy deficiency.

Even more important–how can we prevent The Triad?

The Triad is completely preventable with the right knowledge. Read below for our tips on how to prevent the Triad. All physically active girls and women can do the following to prevent the Triad:

Keep track of your periods – from month to month, writing down the number of days between cycles or use a tracking app

Use online resources – These resources can help you estimate how many calories you need per day to maintain your current body weight

Eat every three to four hours —Three meals a day and at least two snacks. Have a daily eating plan for when to eat to best fuel and re- cover from exercise. For example, competitive athletes often need to carry snacks around during the day and eat before, as well as right after practices. (scheduled/ individualized!)

Treat snacks as mini-meals- Choose foods that are nutritious, taste good and fit your lifestyle. For example, healthy “fast foods” like a bowl of instant oatmeal with raisins, a peanut butter sandwich or crackers with peanut butter, a low-fat milk shake or fruit smoothie, or a micro- waved baked potato topped with cheese, fit the bill

Track how much you exercise in a day– accounting for time, type and intensity of exercise. Adjust your food intake to account for the increased expense of energy. For example if you weigh 150 pounds and you add a 2 hour vigorous volleyball practice to your daily activities, you will burn approximately 1100 calories in addition to your normal requirements. There are many online sources to calculate how many calories are needed by an athlete who performs a wide variety of sports.

- Otis, C.L., et al., American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The Female Athlete Triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1997. [LINK]

- De Souza, M.J., et al., 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br J Sports Med, 2014. [LINK]

- De Souza, M.J., et al., 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition consensus statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, CA, May 2012, and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, IN, May 2013. Clin J Sport Med, 2014. [LINK]

- Nattiv, A., et al., American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2007. [LINK]

- Yeager, K.K., et al., The female athlete triad: disordered eating, amenorrhea, osteoporosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1993. [LINK]

- Gibbs, J.C., N.I. Williams, and M.J. De Souza, Prevalence of individual and combined components of the female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2013. [LINK]

- Drinkwater, B.L., et al., Bone mineral density after resumption of menses in amenorrheic athletes. JAMA, 1986. [LINK]

- Keen, A.D. and B.L. Drinkwater, Irreversible bone loss in former amenorrheic athletes. Osteoporosis Int, 1997. [LINK]

- Warren, M.P., et al., Osteopenia in exercise-associated amenorrhea using ballet dancers as a model: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2002. [LINK]

- Fredericson, M. and K. Kent, Normalization of bone density in a previously amenorrheic runner with osteoporosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2005. [LINK]

- Ackerman, K.E., et al., Oestrogen replacement improves bone mineral density in oligo-amenorrhoeic athletes: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med, 2019. [LINK]

- Singhal, V., et al., Impact of Route of Estrogen Administration on Bone Turnover Markers in Oligoamenorrheic Athletes and Its Mediators. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2019. [LINK]

- Wade, G.N. and J.E. Schneider, Metabolic fuels and reproduction in female mammals. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 1992. [LINK]

- Wade, G.N., J.E. Schneider, and H.Y. Li, Control of fertility by metabolic cues. Am J Physiol, 1996. [LINK]

- Koehler, K., et al., Low resting metabolic rate in exercise-associated amenorrhea is not due to a reduced proportion of highly active metabolic tissue compartments. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2016. [LINK]

- Strock, N.C.A., et al., Indices of resting metabolic rate accurately reflect energy deficiency in exercising women. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, 2020. [LINK]

- Loucks, A.B. and E.M. Heath, Induction of low-T3 syndrome in exercising women occurs at a threshold of energy availability. Am J Physiol, 1994. [LINK]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J., Prevalence of eating disorders in elite female athletes. Int J Sport Nutr, 1993. [LINK]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J. and M.K. Torstveit, Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sport Med, 2004. [LINK]

- Gibbs, J.C., et al., The association of a high drive for thinness with energy deficiency and severe menstrual disturbances: confirmation in a large population of exercising women. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, 2011. [LINK]

- Loucks, A.B. and J.R. Thuma, Luteinizing hormone pulsatility is disrupted at a threshold of energy availability in regularly menstruating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003. [LINK]

- Loucks, A.B., M. Verdun, and E.M. Heath, Low energy availability, not stress of exercise, alters LH pulsatility in exercising women. J Appl Physiol (1985), 1998. [LINK]

- Koltun, K.J., et al., Energy Availability Is Associated With Luteinizing Hormone Pulse Frequency and Induction of Luteal Phase Defects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2020. [LINK]

- Lieberman, J.L., et al., Menstrual Disruption with Exercise Is Not Linked to an Energy Availability Threshold. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2018. [LINK]

- Williams, N.I., et al., Magnitude of daily energy deficit predicts frequency but not severity of menstrual disturbances associated with exercise and caloric restriction. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2015. [LINK]

- Williams, N.I., et al., Evidence for a causal role of low energy availability in the induction of menstrual cycle disturbances during strenuous exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2001. [LINK]

- De Souza, M.J., et al., Severity of energy-related menstrual disturbances increases in proportion to indices of energy conservation in exercising women. Fertil Steril, 2007. [LINK]

- De Souza, M.J., et al., High prevalence of subtle and severe menstrual disturbances in exercising women: confirmation using daily hormone measures. Hum Reprod, 2010. [LINK]

- Zemel, B.S., et al., Revised reference curves for bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density according to age and sex for black and non-black children: results of the bone mineral density in childhood study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011. [LINK]

- Southmayd, E.A., et al., Energy Deficiency Suppresses Bone Turnover in Exercising Women with Menstrual Disturbances. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2019. [LINK]

- Ackerman, K.E., et al., Bone microarchitecture is impaired in adolescent amenorrheic athletes compared with eumenorrheic athletes and nonathletic controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011. [LINK]

- Barrack, M.T., et al., Higher incidence of bone stress injuries with increasing female athlete triad-related risk factors: a prospective multisite study of exercising girls and women. Am J Sports Med, 2014. [LINK]

- Nattiv, A., et al., Correlation of MRI grading of bone stress injuries with clinical risk factors and return to play: a 5-year prospective study in collegiate track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med, 2013. [LINK]

- Tenforde, A.S., et al., Lower Trabecular Bone Score and Spine Bone Mineral Density Are Associated With Bone Stress Injuries and Triad Risk Factors in Collegiate Athletes. PM R, 2020. [LINK]

- Johnston, T.E., et al., Physiological Factors of Female Runners With and Without Stress Fracture Histories: A Pilot Study. Sports Health, 2020. [LINK]

- Nose-Ogura, S., et al., Risk factors of stress fractures due to the female athlete triad: Differences in teens and twenties. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 2019. [LINK]

- Drinkwater, B.L., et al., Bone mineral content of amenorrheic and eumenorrheic athletes. N Engl J Med, 1984. [LINK]

- Rencken, M.L., C.H. Chesnut, 3rd, and B.L. Drinkwater, Bone density at multiple skeletal sites in amenorrheic athletes. JAMA, 1996. [LINK]

- Nose-Ogura, S., et al., Low Bone Mineral Density in Elite Female Athletes With a History of Secondary Amenorrhea in Their Teens. Clin J Sport Med, 2020. [LINK]

- De Souza, M.J., et al., The presence of both an energy deficiency and estrogen deficiency exacerbate alterations of bone metabolism in exercising women. Bone, 2008. [LINK]

- Southmayd, E.A., et al., Unique effects of energy versus estrogen deficiency on multiple components of bone strength in exercising women. Osteoporos Int, 2017. [LINK]

- Zanker, C.L. and I.L. Swaine, Relation between bone turnover, oestradiol, and energy balance in women distance runners. Br J Sports Med, 1998. [LINK]